The dichotomous relation between the two extremities of any religion, however rigid be its structure or dogma — between the formal, scriptural version on the one hand and the plethora of practices and rituals that pass off as the ‘little’ or popular tradition on the other — have never ceased to enchant the observer and entice the researcher. Depending on their individual world-views, scholars have observed and commented on this fascinating dialectical process, often as the interplay between the forces of conformism and autonomy, and have occasionally discovered hidden virtues and delightful facets. The Dharma cult of the western tract of Bengal, that arose centuries ago from among the autochthones of the region, continues to remain considerably their worship even till today — in spite of the tireless attempts of formal Hinduism to ‘standardise’ it. The Juggernaut of the ‘great tradition’ of India, that has successfully subjugated and subsumed almost all the other ‘minor’ deities and religious practices lying in its path, appears to have met its match in this obscure cult of the poorest and the marginalized autochthones of Bengal. The saga of Dharma’s resistance to many of the crucial tenets of ‘high’ brahminism, not by theological debate (which its semi-lettered adherents were hardly capable of), but by practice — carried out mainly under the supervision of an alternate priesthood that emanated from the humble folk and ‘outcastes’ of western Bengal — is the subject of this researcher’s study (with varying degrees of concentration) for nearly three decades. And among the tales of ‘defiance’ to the dictates of the ‘great tradition’ of India that this cult hardly talk about, the one that is the focus of this article is the dogged refusal of the Dharma worshippers to adopt a ‘human’ face (or body) that brahminism has insisted upon, from each peripheral ‘religion’ as the price for its admission into the Hindu fold.

What then is the ‘idol’ of this male deity and how does Dharma look? On both counts, we come across strange responses, for there is no idol of Dharma, not even in his sacred and liturgical texts, on the basis of which the makers of any ‘image’ could sculpt their work. One of the absolutely essential features of brahminical acceptance of deities from outside its original jurisdiction is, as we said, that the god or goddess concerned would lend itself to a graphic visualisation and some type of standard imagery — as some sort of a human or animal, or even both. The more the layers of justificatory or associative myths that cover and secure the deity’s entry into, and the gradual improvement of its inter se position within, the Hindu pantheon, the more is the variety of ‘poses’ that the deity strikes and the greater becomes the diversity of its imagery. This entails that even if the deity in question were originally bereft of any shape or style at the point of entry into formal Hinduism — literature, iconography and priestly sanctification would ensure that at least one style of icon would soon emerge, maybe in addition to an ancient ‘aniconic’ symbolic representation.

But before we enter the world of Indian iconography, we may glance briefly at the position in other countries. The Encyclopaedia Britannica classifies iconographic motifs into five major types1 : (i) the human-faced or bodied, the anthropomorphic; (ii) the animal-shaped or theriomorphic; (iii) the plant forms or phytomorphic; (iv) the hybrid representations that combine elements from the preceding three and (v) the chrematomorphic, which deifies symbols, like the cross, the crescent and the trishul, or objects like the Bible, the Koran or the Zend Avesta. Very useful, but where do we fit the shapeless piece of stone (or wood, in other cults, like Stambheshwar-Jagannath2 ) that is revered as a representation of god, with immense fervour, in the cult of Dharmas? Semitic religions and their studies could not be expected to be familiar with what they have lumped together as “stocks and stones”, unworthy perhaps of further academic investigation3 , at least not as an ‘iconographic’ form. In fact, Hastings’ ‘Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics’ describes4 aniconic representations with exactly these words: “Man may originally have worshipped animals or even stocks and stones, as the fetish-worshipper does.” The encyclopaedia then goes on to elaborate the subsequent three stages through which man passes, at least where Semitic religions were concerned, to reach the fourth and final stage, when god is considered as an abstract goodness, without human-like limbs and body. Let us see what Hastings had to say of the intermediate two stages. “In the second stage of this evolution, not only did aniconic objects of worship become iconic, not only did pictures and statues of the gods…drive out the stocks and stones….of the older cults, but the very conception of the god….become more and more definitely human.” It is then noticed that anthropomorphisation has resulted in gods become ‘too human and less divine’ and thus “the third stage …is reached when religion comes out to denounce the idea that the deity has a body or limbs like a man or an animal…. And religion becomes iconoclastic and ceases to be anthropomorphic.”5 Except for Islam, which too has some element of chrematomorphism6 , neither of the other two Semitic religions could, at the level of the masses, root out iconism or its manifestations through the different ‘morphisms’.

In Hinduism, religious beliefs like monotheism, obeisance to an abstract divinity, aniconic worship and the five morphisms7 — have all co-existed with relative ease, throughout the ages. The Dharma cult itself has contradictory but historic elements from a non-iconic, Sunyavadi tradition (the worship of god as a formless, void), a strong aniconic practice, some creeping shadows of anthropomorphism, a few shades of phytomorphism8 as also a sprinkling of chrematomorphism9 . But restricting our present focus to just the dialectical interplay between just the aniconic and the anthropomorphic, may simplify our approach. The vast repertoire of sacred imagery and iconographic literature that crowds the three major cults within mainstream-Hinduism, appear to have either permitted these cults to transcend their ‘primitive aniconic stage’, relics of which are visible even today. Or, these cults may have subsumed minor or parallel cults that centered round aniconic representations of the relevant omnipotent godhead. It is too late in the day to prove with certainty which postulate is more correct, or whether parts of both hold good, in different spatial and temporal contexts. The task is made all more difficult because academics, right from TA Gopinath Rao10, the pioneer of Hindu iconographic studies, have been true to our western legacy (where aniconism was hardly any concern since the organised religions tolerated only the five ‘morphisms’), and have almost avoided any description11 the pre-morphic, aniconic phase. They thus tend to jump straight into the descriptive analysis of icons, their variations, the symbolism of each detail and so on — either as their tribute to their artistic/stylistic excellence or as their homage to the deities of grand Hinduism, ignoring almost totally the aniconic stage. A few sharp analysts have, however, a few scant words for the entire primitive aniconoc stage. RG Bhandarkar,12 for instance, confers some thought on this, when referring to the absence of the Shiva-linga in the coins of Shaivite kings in the early years of the Common Era, he writes thus, in 1913: “But this element must have crept in early enough among ordinary people, who were in closer communication with the uncivilised tribes, and gradually made its way to the higher classes, of whose creed it subsequently became an article (of worship). And it is this final stage of its adoption by the higher classes that is represented in Upamanyu’s discourse (Anusasana Parvan, chapter 14, where Krishna recounts the glories of ShivaMahadeva) in the Mahabharata.” Such scholarly insights into how the aniconic sacred symbols of the autochthones were subsumed by different cults of ‘high’ Hinduism, and then justified through holy scriptures, are rather rare.

In his lengthy treatise on Hindu iconography, J.N.Banerjea13 came out somewhat more transperantly, stating: “Deities were not always iconically represented; over and above their concrete representations in anthropomorphic and, rarely, theriomorphic forms, they could also be figured in an aniconic manner. The latter mode is reminiscent of an earlier practice. In India, iconism and aniconism existed side by side from a very early period, and this feature is also present even in modern times. Brahmanical cult deities could as well be in Salagramas, the Bana-lingas and the Yantras, that are primarily associated with the Vaisnava, Saiva and Sakta cults respectively, as in images. But here, however, their association with the symbol was not so direct.” He provides an interesting clue to the process of appropriation or subsumation of primitive worships, with special reference to that by the Sakta cult. “The well-known Sakta tradition about the severed limbs of Sati falling in different parts of India and about the latter being regarded as so many pitha-sthanas (highest sites of pilgrimage), particularly sacred to the Sakti-worshippers, should be noted in this connection.” Banerjea does not carry on further, except in giving a few closing hints, mentioning the aniconic stones, covered with vermilion, that are now worshipped at the sites as those ‘fallen limbs’ or as the powerful matrikas — but he does not call the process ‘appropriation’ of primitive forms of the mother goddess by the ‘higher, better-organised religious order’. We have to draw our own inferences, for this set of actions that, in effect, constituted the ‘taking over’ of all the important sites of devi worship, which lay outside the borders of the ‘core-Hinduism’ of the Gangetic Aryavarta, ‘the land of the Aryans’ — with appropriate mythopoeic assistance from the Devi Mahatmya of the Markandeya Purana and the later versions of the Daksha Yagna legend.

Thus, even with the relative paucity of academic treatises on the sensitive subject, we can safely deduce that the hordes of small, semi-cylindrical stones (or their imitations) that pass for Shiva’s phallic lingas; the aniconic pebbles that represent Vishnu’s ‘shalagram shilas’ 14 and the crude stones smeared with scarlet paste (signifying devi or shakti) — that dot the countryside of India — are but examples of how the major deities have parallely retained both their respectable iconographic styles and their ancient aniconic symbolisms, quite comfortably.15 We may even be more specific. If one examines the image of the mother goddess at Tarapith in Birbhum (or at several other pilgrim spots), one needs very little imagination to perceive how a crude lump of stone was skilfully anthropomorphised by covering it with some colourful clothes and ‘topping’ the peak with a round brass pitcher as a ‘head’, which was later ‘crowned’. The ‘sacred strength’ of this then-aniconic mother goddess was most likely to have been recognised well before its millennium-old Buddhist appropriation, and obviously, centuries before the later Shakta-hinduization of the site — but it was only the latter that brought in its wake a mandatory anthropomorphic image, quite different from the classical Buddhist Tara. In fact one hears of the ritual ‘disrobing’ of this devi that takes place before dawn for her sacred daily ‘ablutions’, when the original stone is washed after which it is again vested with the ‘royal apparel’ by the priests — before crowds start queuing up for a glimpse of the divine mother. But despite a complete brahminical take-over of another ancient site of the mother cult at Kamakshya in Assam, the priesthood has not yet been able to insert any image to either supplement the aniconic shila or to replace it altogether. It is only fair to mention that efforts are not wanting, for an imaginary picture of a Vaishnodevi-type ‘mother’, claiming to be this goddess is already in circulation, ostensibly to satisfy the endless traffic of Hindu devotees from all over India who may find it difficult to explain to their families as to how an aniconic stone could be such a powerful deity.

It is undeniable that in spite of these dual levels of symbolic exhibition, it is the human-like idols that encapsulate most of what the Hindu deity stands for — buttressed, as all the major divinities are, by an attractive and fortifying multiplicity of myths, legends and sacred stories. Sages have never tired of mentioning that an anthropomorphic image helps the Hindu recall the almighty somewhat easier, but the chief utility of such human forms was probably to assist viewers recall instantly the particular virtue, or the episode from the sacred ballad or epic, with which the divinity is associated. The anthropomorphic representation, especially in an ‘action sequence’, facilitates the process of ‘re-enacting’ the characteristic deeds that are part of the lore of the deity. Shiva, in his tiger-skin skirt (besmeared with ashes) holding his trishul (trident) and riding the bull, Nandi; Krishna driving Arjuna’s chariot, defying hails of Kaurava arrows; the fierce, unstoppable Kali, drenched with blood and garlanded with human skulls; the belligerent Durga slaying the demon Mahishasura — all these images cast in human ‘action frames’ attract ready mass approval, as compared to the dry respect that may be given to an insipid piece of inert stone. No wonder colourful tales that ride the attractive chariots of Hindu legends conquered almost the entire subcontinent, crushing minor resistance from local cults, or better still subsuming them, with just another story being added to the vast repertoire of heroic valour and divine prowess. The short point is, therefore, that the anthropomorphic conversion of shapeless stones into vibrant human images appears to be an essential qualification for a primitive cult-figure’s entry into the Hindu pantheon. Obviously this mandate must have emanated from the guardian priesthood and sole interpreter of ‘high Hinduism’, the brotherhood of Brahmins. Thus it is quite understandable as to why this researcher found that the presiding aniconic, theriomorphic or phytomorphic deities of almost every other folk cult within the area of the study (the western part of Bengal) were found to have been anthropomorphised, fully or largely.

For instance, while Manasa, the goddess of snakes, is still worshipped in the interior as the ‘sij’ plant, perhaps as a remnant of its earlier phytomorphic or dendrolatrous origins, in more urban areas she is offered obeisance either in her theriomorphic imagery as ‘Manasar jhar’ (a sacred pot with snakes crowning it, or something akin to this). In regions where sanskritization has been more successful, we find this deity in her anthropomorphic style, as a lady seated on a duck with snakes all over her. The latter form of anthropomorphism represents the present high-water mark of the deity’s journey from its humble folk roots to the great assembly of Hindu gods and goddesses. Similarly, Chandi of the Mangal Kavyas, appears to have lost her individuality, and has no unique form, as she has been totally subsumed by the exalted mother goddess of ‘high Hinduism’. She is today just one more rupa of sakti — despite frantic attempts of the antyajas to distinguish this folk goddess from the ‘great tradition’, by inserting epithets and prefixes, like Mangal-, Pagla-, Jay-, Olai-, Baghrai- and many others16. Today, except at very rare sites, Chandi’s original phytomorphic, theriomorphic and aniconic representations have given way to the standard images of the pan-Indian Chandi. Even folk gods of lesser importance, like Dakshin Ray of the riverine Sunderbans, has a human face with a distinguished moustache, twirled up at the corners, painted on an upturned clay pitcher — as his trademark and representation. The little-known Ghentu of Haora also assumes a human face, when it is worshipped on the day of its annual festival, as an upturned ‘karai’ (a broad, hemispherical cooking utensil) and a face is etched on its ritually-painted surface, with cowrie shells as its eyes and mouth.

While even lesser gods and goddesses have, thus, succumbed to the temptations to elevate their status in the Hindu Valhalla by surrendering their age-old individuality and allowing themselves to be anthropomorphised, or at least theriomorphised the Dharma cult stands out in sharp contrast, for even half a millennium and more after the first attempts were visibly made, through the liturgical literature and the Mangal Kavyas, to ‘recognise’ and hopefully reorganise on brahminic lines, this cult of the marginalized people of western Bengal the god of the subaltern continues to retain its aniconic form. To quantify data pertaining to this cult, 272 sites of its worship were studied in western Bengal17 and it appeared that this folk cult has doggedly refused to anthromorphise its deity and oblige the organised brahminism, that has taken over the regular worship at 56 percent18 of the cultic sites from the ‘lower’ castes. Though aniconic does not necessarily mean that it has to be of stone, 95 percent of the sites reported that the god was indeed a shila; about 1 percent of the sites reported that Dharma was represented as a sacred pitcher (ghot); 1 percent as some sort of a image-like object; while 3 percent failed to explain what the deity was made of or looked like19. On the first 1 percent, Sastri had reported, even in 1895,20 “sometimes, an earthen pot filled with water represents the deity”, and had also quoted a Bengali invocation21: “O one who is Narayan in your own form come to this earthen pot and accept my worship.” The fact that the folk-god is sought to be made into Narayan-Vishnu obviously indicates another attempt to brahminise its worship, and it is through these small attempts that one may decipher more of a concerted and active plan of ‘sanskritisation’ by the priestly class — which thus contradicts the Srinivasian postulate that all the activity in the process emanates from the ‘lower’ castes only (in their bid to imitate), while the inert Brahmin does not need to exert himself. To return to the earthen pot, it appears from our present study that this representation of Dharma is actually coming down, in numbers, over the years. But then, this decline could actually have been taking place over a long period, for even in Chattopadhyay’s fieldwork, which was done some sixty-five years ago, we notice that although he has also mentioned the role of the sacred pitcher (which is a common Hindu item of religious ritual) in the worship of this deity in several villages22, nowhere does he mention this ghot itself being used as the deity.

But coming to the other 1 percent of sites which reported that their Dharma had an ‘image-like’ resemblance, we need to take it more seriously. Even the faintest mention of anything close to anthropomorphism may send the first signals that the impregnable fort of aniconism that the deity represents, has started showing small breaches. We have discussed earlier that without a more deliberate strategy to anthropomorphise the deity, its passage to mainstream Hinduism can hardly be facilitated — and without a human imagery, it is hardly possible to remove, or try to obliterate, the traces of autochthonous roots that any such folk deity has possessed for centuries. It is not our view that the Brahmin has always planned or led the process of anthropomorphisation, for other enthusiastic castes (usually of the ‘upper’ ruling strata) and social groups, including nouveau Hindu tribal royalties, have often been more active in such acts — to bring their societies closer to the accepted version of Hindu respectability. But it is most likely that the Brahmin priest has been the prime beneficiary of the conversion to a more agreeable anthropomorphic shape, as he then had a larger client base for the folk god and perhaps felt more at ease, when worshipping a ‘prescribed’ deity rather than a shapeless clod of a stone from some peripheral cult. Before and during my field survey, I managed to visit within my research area every known site of this cult that ever reported that anthropomorphism of this god was being attempted — but could not find a single spot till 2002, where Dharma was converted into a proper human image, or even to some part of it.

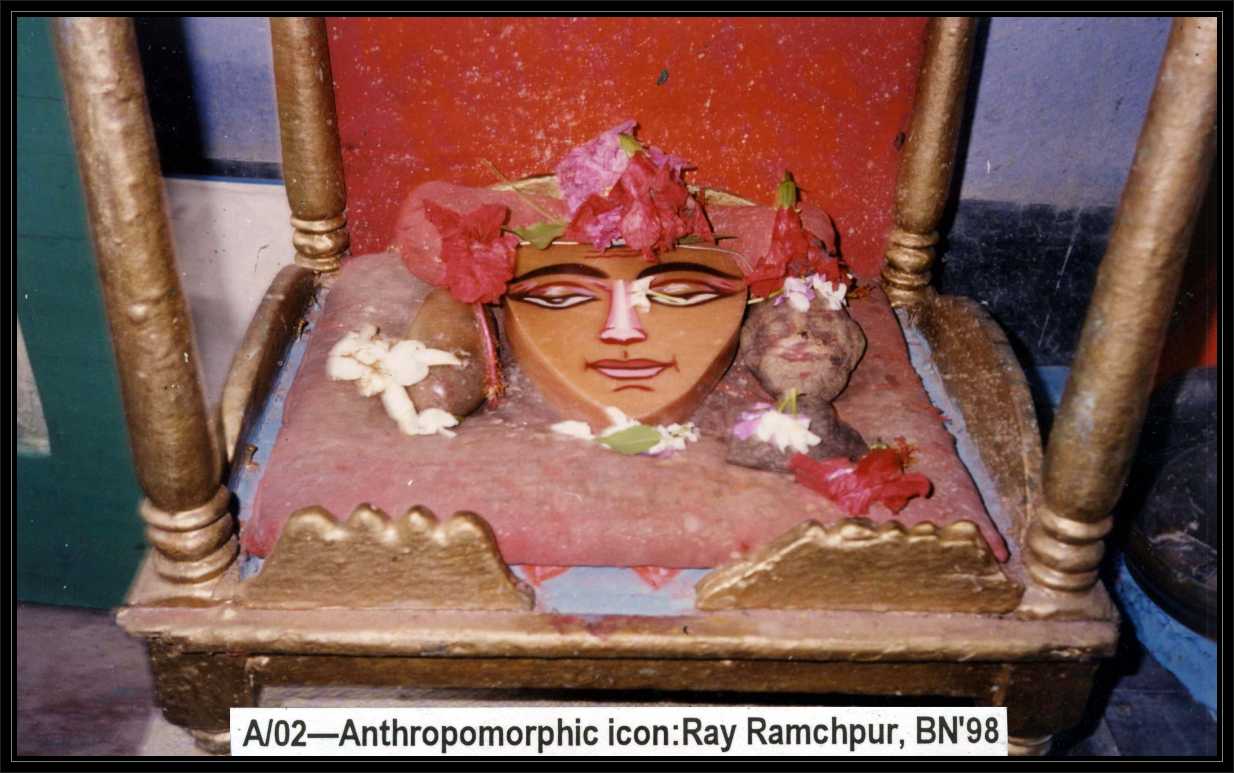

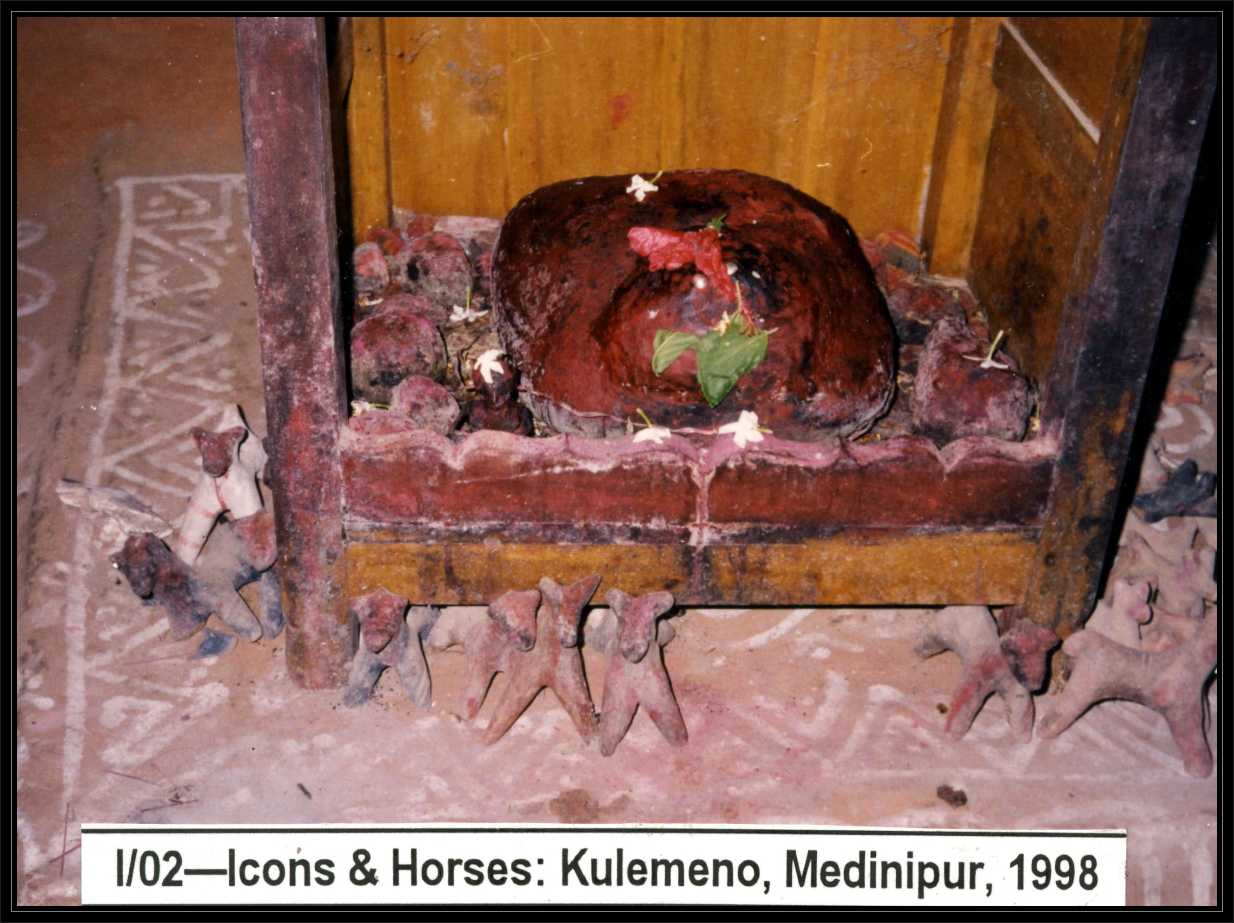

I did, however, come across several attempts to anthropomorphise, which may not have succeeded so far, but there are portents that they may finally win in the coming decades. For instance, in Ray Ramchandrapur village under Bhatar thana of Barddhaman, I saw a piece of stone symbolising Dharma that had slight natural resemblances with a human face. In case people missed this significant variation from the normal dull aniconic shape of the deity, some thoughtful devotee had placed next to the ‘original’ stone another oval piece of cut sandstone representing a human face, with bright eyes, lips and other features unmistakably painted on it. A photograph showing these two face-like stones is placed as Fig.1. At Panchra village in the same district, I found an ingenious combination of three ‘original’ Dharma stones, studded with metal ‘eyes’ (that usually adorn shapeless lithic lumps representing this deity), joined together with clay to look like a human face and two short arms protruding under the ‘neck’. The similarity of this ‘combine idol’ with the standard icon of the Hindu god Jaggannath are striking and most probably deliberate, as we may see from the photograph placed at Fig. 2. Quite often, the ‘real’ Dharma stones are left totally undisturbed while a ‘human head’ penetrates the sanctum as some other deity, such as Mangal Chandi in Unsani, Haora. At other times, it is discovered that a ‘hero’ associated with the cult (from the story of the Dharma Mangal) like the warrior, Kalu Ray, at Ranichak near Tamluk in Purba Medinipur, at Khairakuri in Mohammad Bazar p.s. in Birbhum and at Bargachia under Jagatballavpur thana of Haora. The resilience of the cult becomes most pronounced in this domain, for not in one site did one come across, any such human ‘head’ or face-like stone had been placed beside the primitive anicon, that claimed to be actually representing Dharma — at least till 2003, Even so, the very fact that such an act is likely to mislead the ‘new’ worshipper or visitor, which includes the later generations of the ‘original’ families of devotees, into confusing these human countenances for the deity is perhaps a calculated gambit. In any case, our study reveals that only a very insignificant fraction of the deity’s shapes are even reported to be ‘image like’ or ‘face like’.

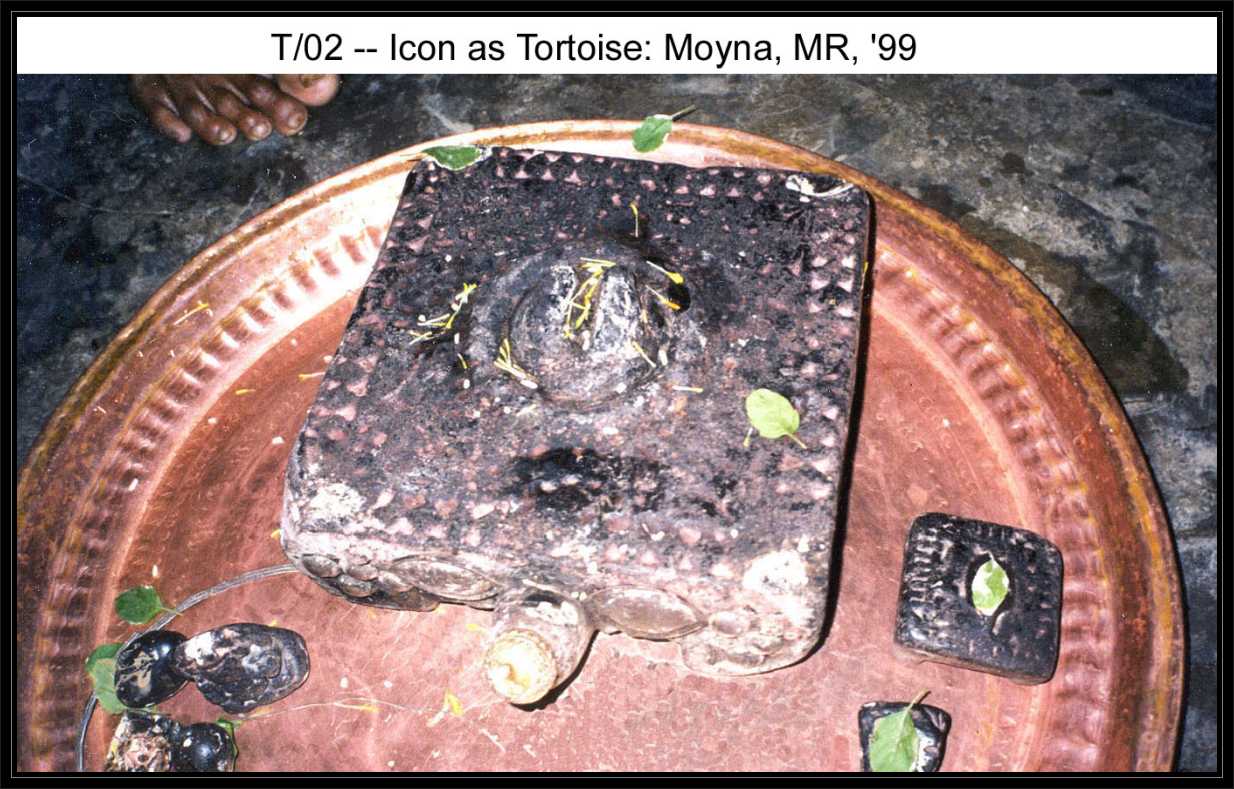

What then are the shapes of the aniconic stone shilas that were reported from 245 villages as the most frequent representation of Dharma (the 95 percent)? Responses to this query were received from 237 of the total such sites23, which is quite good. The largest percentage (30) mentioned that it resembles the tortoise. Here again, one is reminded of the scholarly debate that was triggered off by Haraprasad Sastri in 1894, when he claimed that the Dharma cult was Buddhist in its origins, inter alia, on the ground that the tortoise shape of Dharma represented a Buddhist ‘chaitya’ or the ‘stupa’, the hemispherical prayer hall or the sacred mound of the Buddhists. Sastri remarked, on the basis of a report from his assistant, that the tortoise (which he presumed was round-shaped) “has the legs and the head, these five things representing the shrines of five Dhyani Buddhas” 24. What Sastri’s assistant did not report to him was that the tortoise in Moynagarh (in Purba Medinipur), which I was shown with considerable piety by the former raja, the erudite Pranab Bahubalendra, was almost rectangular, nearer to a square, from which only a head was clearly protruding. The photograph at Fig. 3 brings this out clearly, while Fig.4 shows tortoises carved on square blocks of stone in another place in Medinipur. Sukumar Sen did not agree with Sastri’s identification of the tortoise with the Buddhist stupa, but did not elaborate his logic and simply declared: “Sastri mistook the protruding feet and head of the tortoise to be tiny images of the five Dhyani Buddhas that usually decorate the Buddhist stupa. The cult of Dharma has little to do with Buddhism.”25 In fact, most of the tortoise shapes that I have seen (and photographed) of the deity appeared rather squarish or rectangular, and very few had the perfect shape of a tortoise and one such worshipped at Raipara, Hugli, the photograph of which I place at Fig. 5, is quite rare. Amalendu Mitra26, who had covered a very large number of cult sites in the 1960s, mainly in Birbhum, shared my experience with the different categories of shilas that pass as tortoises.

K.P. Chattopadhyay informs us that the sacred text of the cult, the Sunya Puran, mentions a deity shaped like a tortoise. Hunting for Chattopadhyay’s reference in the Sunya Puran, the only phrase that I could locate (from the ‘Atho Dharmapuja’ section of the ‘Sanjat Paddhati-II’ book), was “heaped on/like the tortoise’s back”27 — which, I feel, refers to the oblations that were being piled on or before the deity. This, Chattopadhyay states as “on the back of the tortoise shaped deity” and unless he was quoting from some other verse, our two interpretations are quite different. We may, however, remember that the ‘cosmogony of Dharma’, that is mentioned in the opening sections of the Sunya Puran, does ascribe an important role for the tortoise — as one of the earliest creatures to be created by the lord, and to have been of great service to Dharma. Suniti Kumar Chatterji refers28 to the importance of the tortoise in Dharma’s story of creation and to the similarity between this cosmogony and those “of some of the Austric/Kol and Dravidian tribes.” In fact, he utilises this clue to derive a notion of the origin of the word, ‘Dharma’, from this creature. One can also locate at least two references to the tortoise in the second liturgical literature composed for the cult, the Dharmapuja Bidhan, mentioning that the lord assumed the form of a tortoise and that this animal and the owl are the vahanas29 (vehicles) of Dharma. As we have discussed earlier, this is not surprising as the literate (Brahmin?) composers of the few ‘sacred texts’ that were constructed for this cult appear to have been influenced, quite considerably at times, by brahminic influences. If anthropomorphisation was not instantly possible, then conferring holiness and legitimacy on a theriomorphic version would be the next best option.

Though much of the discourse on the Dharma cult has assumed or given an impression that the only ‘image’ of Dharma is this theriomorphic representation, some work has also been done to trace its roots. That the Dharma cult may, at some point of history, subsumed the elements from a more universal cult of turtle worship, at least at some places or among some pockets of worshippers, has been discussed by academics, though sparsely. The scholars on this subject so far have mostly been from the Bengali language, with just a few from history and one from anthropology, and they are not expected to be alluding to the

One of the reasons that prompted me to ascertain the actual position of this worship through my field survey was to confirm or rebut, with statistics, the overwhelming academic opinion on different aspects of the subject — one of which stated that the only or most frequent shapes in which Dharma shilas were found was that of the tortoise. Sukumar Sen30, for instance, declared, “The emblem of Dharma is a tortoise. In most cases it is a natural bit of stone shaped like a tortoise; in other cases, it is a chiselled stone image of the same.” While one can overlook the statements made by Sastri, who has mentioned (in his writings that were directly on this cult), that he personally visited just a few sites or even the scholars of the Bengali language and such other urban scholars of the Bangiya Sahitya Parishat and the Asiatic Society, but we do find it a little difficult to accept a particular observation of a field-toiling anthropologist like K.P. Chattopadhyay. His statement, after studying in detail a dozen or so sites of the cult in the westernmost portion of Bengal in the late 1930s for detailed fieldwork was: “Most of the images of Dharma which the writer observed in the districts of Birbhum, Midnapur and 24-Parganas were shaped like tortoises.”31 What the statistics of our study of a large number (in fact, the largest so far) of Dharma sites revealed was that only in 30 percent of the sites is this cult deity shaped like a tortoise. Or, to be more precise, in 30 percent of the sites of the cult from which we have relevant information, at least one of the shilas representing Dharma at the sites was shaped like a tortoise. This makes the position far different, for we may bear in mind that the number of shilas, of all sizes and shapes, that are there at any given site may be over ten or a dozen, each with a distinct name. Thus, if we had some method of totalling the entire lot of Dharma shapes, we may have come across the tortoise-shaped god in just a small fraction of the sigma, far below 30 percent.

Though much of the discourse on the Dharma cult has assumed or given an impression that the only ‘image’ of Dharma is this theriomorphic representation, some work has also been done to trace its roots. That the Dharma cult may, at some point of history, subsumed the elements from a more universal cult of turtle worship, at least at some places or among some pockets of worshippers, has been discussed by academics, though sparsely. The scholars on this subject so far have mostly been from the Bengali language, with just a few from history and one from anthropology, and they are not expected to be alluding to the anthropological literature on the latter aspect, though Mitra has. I feel he is correct when he state that the tortoise is quite likely to have been a primitive totem that was later deified and subsequently subsumed by the Dharma cult. He has drawn freely from the literature on this subject and presents an interesting view that this amphibian creature’s importance lay considerably in its ‘magical’ role as a rain inducing ‘charm’32. Rahul Peter Das, who generally criticizes Mitra’s amateurish approach, is more comfortable with the school of thought represented by Asutosh Bhattacharyya (1939), Sukumar Sen (1945) and Shashibhusan Dasgupta (1946), which has been followed quite ‘religiously’ by most later scholars — that Dharma is a combination of several Hindu and also a few non-Hindu or pre-Hindu deities. According to this theory, the tortoise is symbolic of the three Hindu gods, the sun god, Surya, because both are circular; Vishnu, because one of his incarnations is a tortoise, and also Varuna, because he is associated with rain, like Dharma.

Coming to western scholars, we find as early as 1869, Inman33 voicing the view that “the resemblance between this creature’s (protruding) head and neck and the linga, (is) why both in India and in Greece the animal should be regarded as sacred to the goddess personifying the female creator, and why in Hindoo myths it is said to support the world.” A century later, Hastings would clarify that the tortoise or turtle “is one of the mythical animals on which the world rests, both in Asia and in America.” From the Iroquois Indians in the new world to the Mundari Kols in old India, from the island of Madagascar to that of Java and some Pacific islands, the turtle is either worshipped or held as a ‘tabu’. Except for the Zorastrians of Persia who deem it to be an evil creature34, for others it is not too long as step to take from reverence to worship, and we can visualise a godhead emerging in some sort of an iconic manner. Thus the Vishnu cult most probably subsumed the worship of the kachhua or kacchapa prevalent among the autochthones of ancient India, by associating it with one the great rishis (sage, titular founder of a lineage), Kashyapa of the Vedic era and also admitting it as the Kurma avatar or the ‘tortoise incarnation’ of Vishnu35 .

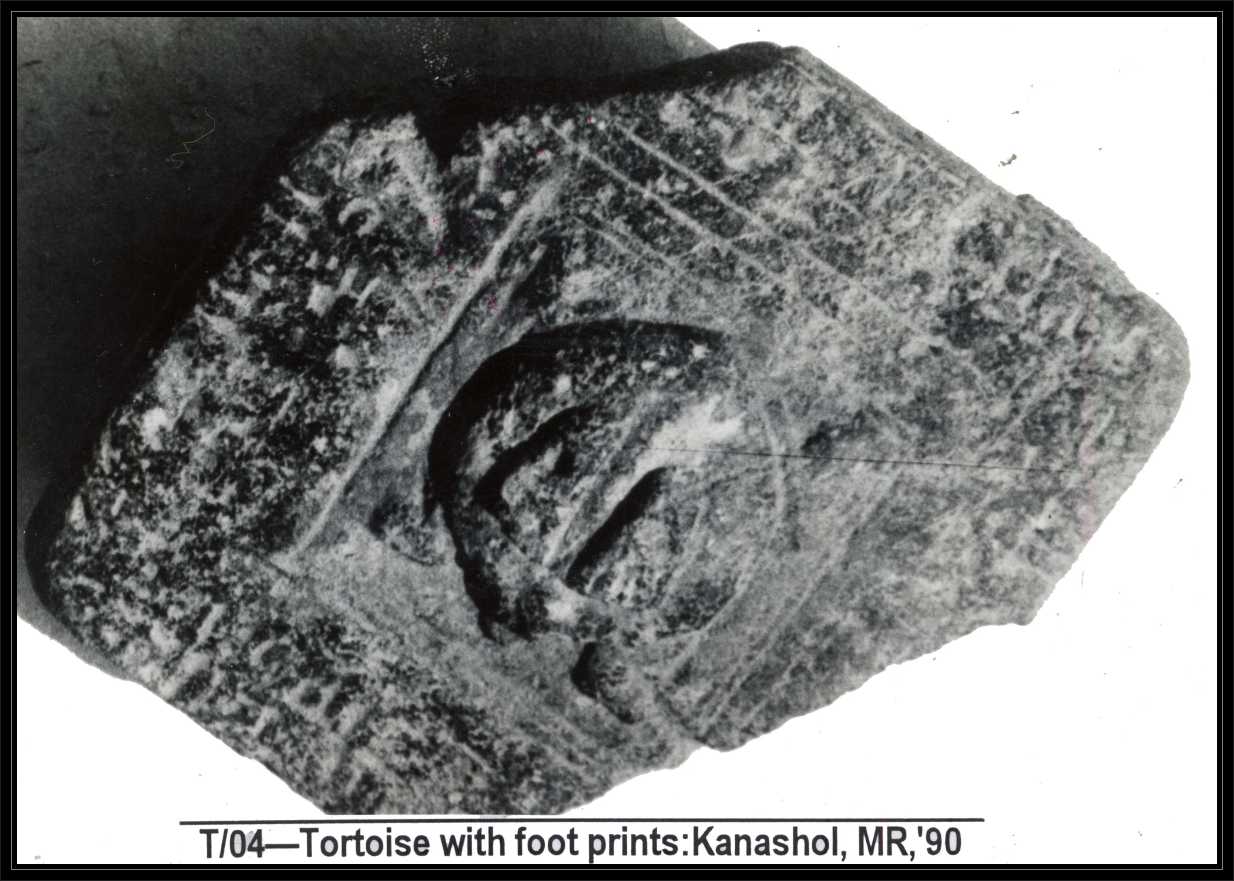

It is possibly to reinforce this Vaishnava identity that the typical pair of ‘footprints’, so very much like those of Vishnu’s, often appear on the backs of the tortoises representing Dharma, like the pair that I have captured on film and shown as Fig. 5. In fact, as Sen has remarked: “the emblem of Dharma, rather his padapitha or footstool on which was placed or engraved the paduka (footwear: boots or sandals) of Dharma is a tortoise.”36 France Bhattacharya is emphatic that these padukas represented, along with other regal trappings, like the throne, the umbrella, the stick and the horse, the five symbols of royal power and authority37 in medieval western Bengal, through this popular cult of the masses.. The pair of footprints appears, however, to be no monopoly of any religion or state, for Buddhism has it in full measure all over its beat, and Islam too has its own ‘footprints of the prophet’, the Kadam Rasul. One could always argue that these footprints represent, like the tortoise itself, the strong Buddhist connection38 of Dharma worship. But whether Buddhist or not, it is undeniable that the worship of the footprints of Dharma, or more specifically his sandals, does occupy an important position in the cult. Chattopadhyay reports these ceremonies from several villages, like Maynapur in Bankura and Birsinha in Medinipur39. Besides, as he mentions, the worship of the deity’s sandals constitute an essential element in the procedure of worship laid down in the Sunya Puran40 .

The fact that our study revealed that the vast majority of the sites did not have any tortoise image, proves that field studies are required, especially when the debate on a rural social practice gets too heated among the urban intelligentsia. Before we close the discussion on this issue, we may carefully examine the list of 72 sites, revealed in our study of 272 sites, where Dharma is worshipped as a tortoise — for leads and patterns that may emerge. It becomes clear quite soon that this worship is not confined to any particular region, but spread fairly evenly, in the sense that it is found in all the districts of the state west of the Bhagirathi under study, except Purulia, which was not traditionally

To return to our postulate on theriomorphism, we have to admit that it is quite a simplification of the otherwise-complex world of animal cults, which, as Hastings has pointed out in a lengthy commentary41, has immense variations — from holding a whole species to be sacred to according this honour to a select few of the species. “The term ‘worship’ and ‘cult’ are used, especially in dealing with animal superstitions, with extreme vagueness. At one end of the scale we find the real divine animal, the ‘god-body’…at the other end, separated from the real cult by imperceptible transitions, we find such practices as respect for the bones of slain animals.”42 But though the tortoise representation of Dharma may be a significant aspect for examination and deliberation, the study reveals that only a small fraction of the Dharma shilas look like this animal.

The fact that our study revealed that the vast majority of the sites did not have any tortoise image, proves that field studies are required, especially when the debate on a rural social practice gets too heated among the urban intelligentsia. Before we close the discussion on this issue, we may carefully examine the list of 72 sites, revealed in our study of 272 sites, where Dharma is worshipped as a tortoise — for leads and patterns that may emerge. It becomes clear quite soon that this worship is not confined to any particular region, but spread fairly evenly, in the sense that it is found in all the districts of the state west of the Bhagirathi under study, except Purulia, which was not traditionally part of Bengal. On closer examination, however, there seems to be some amount of ‘density’ of these specific sites in some areas, though these can hardly be called concentrations as these sites could very well be surrounded by sites with other types of shilas While we do not find any specific ‘region’, covering two or more contiguous districts, or their parts, we do discover that there is a large number of sites in certain pockets, like the Ghatal subdivision of the present Paschim Medinipur district, especially Chandrakona thana in its northeast corner. In the contiguous Haora and Hugli districts, the sites are somewhat better distributed, but even in these districts, more sites are found in the western halves, while in Bankura no real pattern emerges. In Barddhaman, it is their eastern part of the district that has more sites with the god shaped as a tortoise, and no such site at all in the central and western parts of the district, at least not in our survey. Birbhum has comparatively few sites, mainly in the south. These trends do not indicate any worthwhile cultural information, which could be developed: on the other hand, it vitiates a postulate that I had tried to prove that the tortoise-god was to be found more near the rivers and watery areas, that were developed by the fishermen castes (Jeles) into agricultural belts, as they became more ‘peasantised’43 .

The remaining 70 percent of findings regarding the ‘shapes of shilas’ still await our attention, and none of them are theriomorphic. The next major group of these aniconic deities, i.e., 21 percent appears as ‘round-shaped’, which is at least better than finding any random or bizarre shape. But as the broad term ‘round shaped’ could mean anything to the enumerators who filled in the Questionnaires, any smooth shila that appeared somewhat round or oval could come under this category, and our very common Dharmas that are placed at Fig. 6 are typical of this category of smaller pebbles. The hemispherical ‘stupa’ shape (more or less) as visible in the shila in the foreground of Fig 9 accounted for the third largest group, which is 18 percent and if we add this 18 to the 30 percent of kurmaakar (tortoise shaped) ones, we may find that Sastri may have had a small point, not when he said that most of the deities are ‘tortoises’, but when he claimed that the hemispherical Buddhist stupa may have influenced the contours of the god-head. The tortoise shown in Fig. 5 has such a shape, but then, as mentioned, many if not most of the kurma-shaped Dharma ‘icons’ were not round-shaped, but more like a square or a rectangle, like those at Fig.s 3 and 4. Thus we find that much less than half the shilas have any resemblance to the shape of a Buddhist stupa or chaitya. The photograph on the plate at Fig. 7 will show a lumpy shape of the deity, but its shape is more ‘square’ and at the same time there is a protruding ‘head’ which may qualify this anicon as a ‘tortoise’.

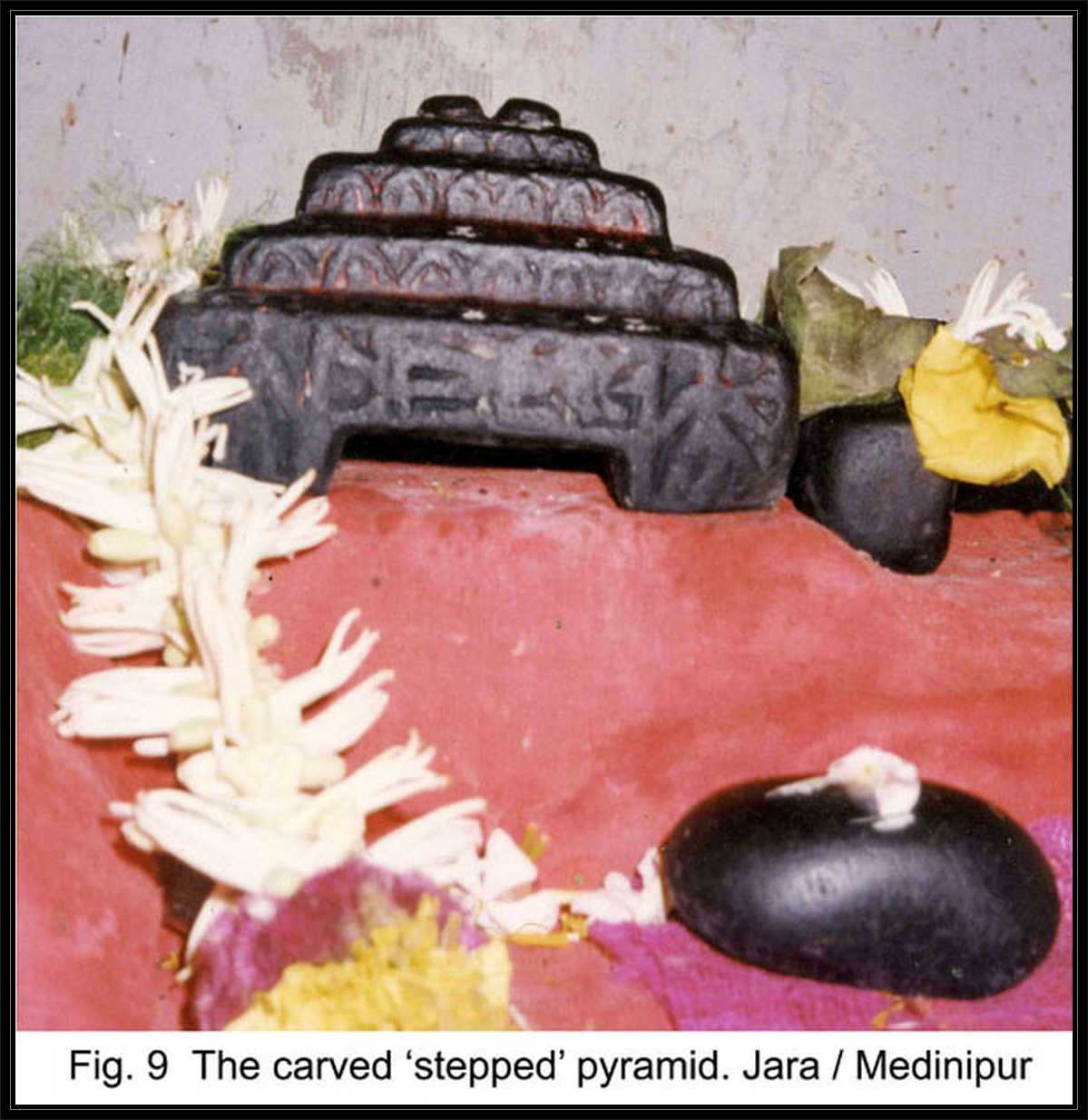

In fact, the results of the field survey bring out that about 11 percent of the sites reported the god to be shaped either as a rectangle or as a square. Fig.s 4 and 8 of the deity at Amodpur in Medinipur and at Fuli in Hugli district, respectively, are good examples of this shape. But with a choice of 10 shapes that the ‘boxes’ in the Quetionnaire offered the field workers (to tick), it is quite likely that they may have used their own imagination/visualization in denoting the shape of the deity that they saw it — especially as some anicons belonged to more than one group/‘box’ that appeared in the Questionnaire. I had seen quite a lot of the ‘pyramid’ type of stone Dharmas during my field visits, but this survey revealed that only in 3 percent of the sites did Dharma look like a pyramid. A certain percent of the reported 11 percent that went in favour of the rectangles/squares, may actually have been ‘pyramids’. This will be clear once we take a look at two such Dharma ‘images’ photographed in villages of Chandrakona thana of Paschim Medinipur, shown as Fig.s 9 and 10. These steppyramids, that look like the Inca-Aztec temples or the massive one at Angkor Vat fascinated me, but none of the villagers could explain as to why Dharma had this shape. Even the two oft-quoted sacred texts44 are of little help in such matters as, unlike late Buddhism or Puranic Hinduism, this cult has no text-icon relationship.

But before we move on from these two step-pyramids, we may admire the beauty of the stone carving that has been executed to produce them, as also the delicate sculptural skills that are so clear on the stone anicons that appear at Fig.s 4, 5 and 8. Two deductions come out with reasonable clarity: the first that all Dharma anicons are not found in their natural state, for some like these have been crafted upon; and the second that all aniconic shilas do not necessarily have crude natural shapes, but some are quite artistic creations, like many of the icons. The second requires to be emphasised upon, as an important advantage that often appears in favour of icons (and their varied depictions) is that icons/idols permit the artistry of a people to flourish at a high level, as painting, sculpture and other arts are doused in religious piety. My simple statement is that aniconic deities also offer such avenues, as is displayed in the craftsmanship of those shilas that appear in the plates just mentioned

Another 10 percent of these aniconic deities is accounted for by the ‘elongated’ shilas category, in which the ‘cucumber’ shape is more pronounced. This particular type of shape has been rather useful to the Brahmin priests in declaring many of these Dharmas to be lingas of Shiva and wasting, as little time as possible, in moving their identity in the direction of the great god of the Puranas. As an example, I submit the photograph in Fig. 11, taken by me at Mohanpur in Birbhum where this elongated or linga-type Dharma is kept erect, with the help of a pillow supporting it from the rear. It is not as if that this ‘propping up’ of the aniconic stone is a rare occurrence at Mohanpur, for our study reveals that in 47 percent of the sites, the shilas 45 (whatever be the shape of these anicons) are positioned in an upright mode. It is my considered guess that, in sites such as Mohanpur where the Dharma’s shape is so similar to a Shiva-linga, once the Brahmin priests have tested the waters for their claim that upright aniconic stones are in fact Shiva-lingas, some faithful devotees will then gift the temple with a metal or stone Gauri-patta (the matching platform, signifying the female genital, on which the linga stands erect) — as their tribute to the god, for bestowing some personal favour. Symbolic acts like these help convert the Dharma’s stone instantly into a classic and full-fledged aniconic representation of Shiva and the identity of the gods are ‘locked in’ beyond any argument. One may, therefore, be reasonably justified in feeling that such actions, which help the pan-Indian priestly class actually network46 the minor local deities from the micro level to the macro, within the elastic framework of the ‘great tradition’, constitute the innocuous but ingenious examples of ‘brahminical activism’.

We have travelled quite some distance since we commenced this discussion with the five different forms of ‘morphism’ or representations of the godhead, as distinguished from the aniconic. The coexistence of many parallel forms of such deific depiction, within the overall flexibility of Hindu worship, was then examined — from which it appears undeniable that the anthropomorphic depiction is by far more popular in this religion — possibly because of its inherent capacity to lend itself to graphic portrayal of the virtues of the divinities, as also of the colourful frames that emanate from the large reservoir of Hindu religious myths. Anthropomorphisation of aniconic and other forms of non-human symbolization of different deities would, thus, appear not only more convenient to the pan-Indian priesthood, but gradually to be an essential element of the process of ‘hinduization’ of autochthonous gods and goddesses. The example we chose was Manasa’s where the folk goddess of snakes is first seen as just a specific plant (the phytomorphic); then as a sacred pot (the aniconic) adorned by snakes (the nominally theriomorphic) and finally as an anthropomorphised deity. But unlike other Hindu and transformed folk gods/goddesses, Dharma appears to be resisting all stratagems to anthropomorphise it — we examine these attempts, as well, including the muchdebated tortoise form — and all this, despite a marked brahminic appropriation of a substantial part of its priestly leadership. In examining the micro levels of the ‘little tradition’ at which transformations are actually ‘executed’ in favour of the ‘great tradition’, one can sense the throbbing pulsations of ‘brahminical activism’, which substantially negates the Srinivasian theory of unilinearity of effort in his concept of sanskritization. For, to deny the tireless labours of the local Brahmins situated in every remote corner of this vast country, is tantamount to denying the paramount role of this nation-wide brotherhood of priests in ‘stitching’ their divergent parochial cultural traditions onto the immense collage of Hinduism. It would deny the dues of this varna in creating a palpable ‘unity among diversity’ in a country called India — which would perhaps never have emerged, without the relentless brahminic appropriation of local institutions and without their unparalled management of contradictions.

We end our journey finally at Jamalpur in Barddhaman district, with a unique deity called Buro-raj, which combines the very Bengali Buro-Shiva of formal Hinduism with the Dharma-raj of the original people. As will be evident from the photograph at Fig. 12, it is a commendable ‘joint venture’ that only brahminical ingenuity could produce, to legitimise its subsumation of the most popular and well-known site of Dharma worship in the western tract of Bengal. It involved, maybe because of its importance as a site of assured pilgrim traffic, the unusual act of superseding the original Dharma-shila with a later and more exciting brahminical ‘discovery’ of a Shiva-linga. It also involved the crafting an unique pedestal to accommodate both the new Shiva’s crude rock and the old Dharma’s symbolic representation, as one of the rarest ‘sunya’ or void images that one comes across anywhere in India. But such a ‘physical’ manipulation of the deity does not seen to be a common practice for the all-India priesthood appears to have depended more on greater subtlety for ensuring an easier acceptability, and on semiotical interjections, mythopoeic constructions and interpolation of rituals to fortify its discreet acts of appropriation. While the process of hinduization of non-Hindu or pre-Hindu forms of worship has been rather uneventful and largely uncontested, the fact that a folk deity of a marginalised people, called Dharma, has not yet yielded to the compulsory brahminic prerequisite of anthropomorphising its aniconic god stands out, in contrast, as one of the most impressive expressions of autochthonous autonomy.

Notes

1 Micropaedia (1981), vol. 17, pp. 906-08.

2 See Eschmann (1978) for the coversion of the worship of the wooden stump or pillar, the Stambeshwar or Khambeshwar (or its feminine gender) into the state religion of the Utkalas, Jagannath.

3 There is a rare and fascinating account of ancient pagan and modern Christian symbolism in Inman (1869)

4 Hastings (1974), vol. 1, pp. 573-4.

5 All quotes are from Hastings, ibid.

6 As in the worship of the Koran.

7 There is a good ‘religious interpretation’ of this subject, which though far from analytical in the anthropological sense of the term, may be of some use to understand the Hindu psyche, in Swami Nityananda (1983).

8 The worship of the Gamar tree (Gmelina arborea) and the ceremonial cutting of its branch during the annual festivities is a practice among some groups of Dharma worshippers. (Chattopadhyay: 1942. p.120)

9 Deification of objects like the Baneshwar, the holy plank studded with nails, for self-mortification by the devotees.

10 Elements of Hindu Iconography, Travancore, 1914.

11 Gopinath Rao hastily skips over a brief narrative of the ‘salagramas’ (“generally a flinted ammonite shell, which is river worn by the Gandaki and thus rounded and beautifully polished. Each has a hole, through which are visible several interior spiral grooves resembling the chakra or discus of Vishnu”. pp.9-10) and one on the bana-lingas of the Shaivas (“mostly consist of quartz and are egg-shaped pebbles, ranging from the eighth of an inch to one cubit.” i.e., 1.5 feet. pp. 11-12)

12 Bhandarkar (1913), p.113.

13 Banerjea (1956), pp. 82-83.

14 Shila signifies a ‘rock’ and could range from the humble pebble to the larger lump of stone. It appears to have, in the domain of religion, some connection with the sacred obelisk or menhirs worshipped or revered elsewhere in the world.

15 For an introductory reading on the ‘Aniconic and Anthropomorphic’ in the religion of ancient Greece, one may find Moore (1977: 78-83) quite interesting.

16 Chaudhuri Kamilya (1992), 2nd edition, 2000, pp. 190-93, for a detailed discussion on the names and imageries of Chandi, the folk goddess.

17 This survey was sponsored by the Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi, for a large area covering parts of seven districts of western Bengal and was carried out by trained fieldworkers using a preplanned Schedule/Questionnaire. It was conducted under the supervision of the present writer between mid-1999 and 2003.

18 Response to query no. L.3 of the Questionnaire that was used in the field survey of 272 sites of Dharma

worship.

19 Results of the replies received against query no. E.2 of the Questionnaire.

20 Sastri (1895c), p. 9.

21 Sastri (1895c), pp. 15-16.

22 Chattopadhyay (1942), pp. 101,107,109, 110, 111, 115.

23 On the basis of replies received to query no. E.5 of the Questionnaire

24 Sastri (1895c), p.21.

25 Sen (1945), p.672

26 Mitra (1966), “The tortoise is quite often etched or carved on the upper side of a square stone.”

27 Chattopadhyaya (1977): Sunya Puran

28 Chatterji (1945), p.79.

29 Bandyopadhyaya (1916): Dhamapuja Bidhan, pp. 90 and 94 respectively.

30 Sen (1945), p.672. Also quoted in Bhattacharyya (1978), p.328

31 Chattopadhyay (1942), p. 105.

32 Mitra (1972) and (1966: 1-6). For their critique, see Das (1983) pp. 661-700. Though Das is dissatisfied with “the often abstruse and sometimes fantastic reasoning of Mitra” (p. 666) and castigates Mitra for “indulging in speculation, using incoherent and incomprehensible arguments ….in connection with rain rites” (p.680), he has a sneaking suspicion that the mandatory, ritual bathing of Dharma (not the tortoise cult as such) is indeed a remnant of the rain rites.

33 Inman (1869), p.99

34 Hastings (1974), vol. 1, p.530.

35 Wilkins (1882) and Knappert (1992) are two of the innumerable books that bring out the justificatory myths of various acts of ‘Hindu’ or brahminic subsumation of indigenous godheads and cults into the vast network of Puranic lore

36 Sen (1945: 672). Mitra (1973: 1) corroborates: “Usually, the tortoise is used as the footrest of Dharma”. I have come across several stone ‘tortoises’ worshipped as Dharma, with these footprints carved on their backs, and as Mitra states, quite correctly, several other such creatures with no such markings on them.

37 Bhattacharya (2000), pp.361-2.

38 We may recall the comment of Hastings (vol.7, p.43) at the end of the last chapter, regarding the empty throne and the footprints of Buddha being the first, early depictions of the deity.

39 Chattopadhyay (1942), pp. 104, 113, 114, 116.

40 Chattopadhyay (1942), p. 102.

41 Hastings (1974), vol. 1, pp.485-91.

42 Hastings (1974), vol. 1, p. 486. 36 Sen (1945: 672). Mitra (1973: 1) corroborates: “Usually, the tortoise is used as the footrest of Dharma”. I have come across several stone ‘tortoises’ worshipped as Dharma, with these footprints carved on their backs, and as Mitra states, quite correctly, several other such creatures with no such markings on them. 37 Bhattacharya (2000), pp.361-2.

43 See Burton Stein (1980): Peasant State and Society in Medieval South India, especially chapter II.

44 Sunya Puran and Dharma Puja Bidhan.

45 Response to Query no. E.7, which also shows that in 50 percent of the 218 sites (from which replies were received), the shilas were kept supine/in a lying down position, while the remaining 3 percent were ‘reclining’.

46 See Cohn and Marriott (1958) on networks and centres in the integration of Indian civilization

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Banerjee, Jitendra Nath. 1956: The Development of Hindu Iconography. Calcutta: University of Calcutta.

- Bhandarkar, R.G.. 1913: Vaisnavism, Saivism and Minor Religious Systems. Orig. Strassburg. Varanasi: Indological Book House, Indian reprint, 1982.

- Bhattacharyya, Asutosh. 1939: Bangla Mangal Kavyer Itihas. Calcutta, 8th revised edition, 1998: A.Mukerji & Co.

- Bhattacharyya, Narendra Nath. 1978: ‘The Cult and Rituals of Dharma Thakur’ in Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya. ed. (1978) : History and Society: Essays in Honour of Prof. NiharranjRay. Calcutta: K.P.Bagchi & Co.

- Chattopadhyay, K.P. 1942: ‘Dharma Worship’ in Journal of Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. VIII, No. 4.

- Choudhury Kamilya, Mihir. 1992: Anchalik Devata: Loko Samskriti. Barddhaman: Burdwan University.

- Cohn, Bernard and Marriott, McKim. 1958: ‘Networks and Centers in the Integration of Indian Civilisation’ in The Journal of Social Research, No. 1.

- Das, Rahul Peter. 1983: ‘Some Remarks on the Bengali Deity Dharma: Its Cult and Study’ in Anthropos, Vol.78, pp. 661-99.

- –– 1987: ‘More Remarks on the Bengali Deity Dharma, Its Cult and Study’, in Anthropos, Vol. 82. pp. 244-51.

- Dasgupta, Shasibhusan.1946: Obscure Religious Cults. Calcutta: Firma K.L.Mukhopadhyay, reprint, 1976.

- Eschmann, Anncharlott. et al. (ed). 1978: The Cult of Jagannath and the Regional Tradition of Orissa. Delhi.

- Hastings, J. (ed.) 1974: Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. Edinburgh: T and T Clark.

- Inman, Thomas. 1869: Ancient Pagan and Modern Christian Symbolism. New York: Peter Eckler, reprint, 1974.

- Knappert, Jan. 1992: Indian Mythology: an Encyclopedia of Myth and Legend. Indian reprint, Delhi: Indus/ Harper Collins Publishers.

- Micropaedia of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1981: 15th edition. London, Chicago: William Benton.

- Mitra, Amalendu. 1972 : Rarher Sanskriti O Dharma Thakur. Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay.

- — 1966: ‘Dharmer Kurma-murti’ in Sahitya Parishat Patrika, Vol. 73, no. 1-4, 1373 B.S.

- Moore, Albert C. 1977 : Iconography of Religions: An Introduction. London, SCM Press Ltd. pp.78-83.

- Rao, Gopinath T A. 1914: Elements of Hindu Iconography, Travancore; 1971 Reprint:, Varanasi: Indological Book House.

- Sastri, Haraprasad. 1894: ‘Discovery of the Remnants of Buddhism in Bengal’ in the Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, December.

- –– 1895a: ‘Buddhism in Bengal Since the Muslim Conquest’ in The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. LXIV, pt.1, No. 1, Calcutta.

- –– 1895b: ‘Cri-Dharma-Mangala: A Distant Echo of the Lalit-Vistara’ in The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, Vol. LXIV, pt.1, No. 1.

- –– 1895c: ‘Discovery of Living Buddhism in Bengal’ in The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, Vol. LXIV, pt.1, No. 2.

- Sen, Sukumar. 1945: ‘Is the Cult of Dharma a Living Relic of Buddhism in Bengal’ in B.C.Law Volume I, Calcutta I.R.I.

- Sinha, Surajit. 1962: ‘State Formation and Rajput Myth in Tribal Central India’ in Man in India, Vol.42. No. 1, May, 1962.

- Swami, Nityananda.(ed), 1983: Symbolism in Hinduism. Mumbai, Central Chinmaya Mission Trust.

- Wilkins, W.J.. 1882. Hindu Mythology: Vedic and Puranic. London. 1994. Second Indian reprint, Delhi: Rupa and Company